The sweet scent of vanilla

Vanilla originally only grew in ancient Mexico, but has now found its way into the Westland greenhouses.

19th century innovation

Vanilla planifolia Tlilxochitl (the Aztec word for vanilla) originally grew only in ancient Mexico. The original inhabitants, the Totonaks, were exceptionally good farmers and were the first to cultivate the now better-known vanilla planifolia, a 15-meter-long climbing vine with fleshy stems and aerial roots. The fruits of the planifolia contain sweet marrow that the Aztecs added to a cocoa drink to make it less bitter. Perhaps this was the original chocolate milk recipe.

Vanilla is a complicated product to produce, mainly due to the pollination of the flowers. It can take up to 3 years for a vanilla plant to give its first flowers and in nature the vanilla orchid is pollinated by a tropical bee, which is only found in Central America. When the Spanish conquistadors (conquerors) first brought vanilla to Europe, they were unable to grow it due to the absence of the insect. It was not until the French took the vanilla plant with them to the island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean that the odds changed. There the slave boy Edmond Albius managed to pollinate the vanilla flower with a bamboo stick. This innovation made Réunion the world's largest producer of vanilla within 50 years. After pollinating the flowers, the ovaries swell into long green pods containing thousands of tiny black seeds. It is these pods that turn black after a lengthy drying and treatment process (curing); the color that makes us immediately recognize vanilla as such.

A fascination for years

Growing vanilla is a completely different process from the fast-growing cresses that Koppert Cress is known for. Rob Baan says enthusiastically: “I have been fascinated by vanilla for years. We have had a row of vanilla plants in our jungle garden for years and now we have managed to grow these in larger volumes. In the past, the vanilla beans ripened on the plant itself, but this had some drawbacks. The longer a pod hangs on the plant, the more likely it will be damaged by adverse weather conditions, such as typhoons. They then fall off the plant and can no longer be used. Theft is also a problem: the pods are regularly stolen due to their high value. For these reasons, the beans in production countries are actually picked too early. They are just not fully ripe then and that's how you get those thin dried sticks that you buy in the supermarket. We wanted to do better, so we started producing vanilla in Dutch greenhouses. Only in this way can you simulate the ideal growing climate all year round without the risk of unpleasant natural conditions, so that we can optimize production. Growing in a greenhouse is slightly more expensive than in the open field, but in return you are guaranteed high quality, without pesticides or other chemicals. The result? A beautiful, rich and fat vanilla pod.”

It is no surprise to gastronomy that products with real vanilla can be recognized by the black dots. If there are no black dots in it, but it does taste like vanilla, then the taste is an unnatural and chemical product. To make it even more confusing: sometimes particles are even added so that it is almost indistinguishable from the real thing. Rob: “The vanilla flavor vanillin, which can be found in, for example, vanilla custard, is chemical. It is cheaper, but made from petrochemical products. We want to achieve true pricing by producing our own vanilla; the product has to be right.”

The early bird...

As a result, Koppert Cress had had the ambition to put vanilla on the market for years, but lacked the understanding of cultivation, the patience and the space to achieve this. “Growing vanilla is by no means an easy job.” says Bart van Meurs who's lived in Westland all his life, of the vanilla project team. “That's why good cooperation was an absolute must. We found a partnership in the experienced and patient experts from another family business, a third and fourth generation grower of cut orchids. The first plants were purchased in 2017 and the family has continued to cultivate the vanilla from 2018 onwards. The rest is history. We now have quite a few meters of vanilla plants. The total process is one of a lot of patience and working with very skilled people. The technology is completely new and it was always a matter of looking for the right plants and testing and testing again.”

As mentioned before, the pollination of the flower has to be done by hand due to the absence of the tropical bees and, what many people do not know, is that the plant only blooms for a few hours; from sunrise to a little before noon. Bart: “That means that in February you have the time to pollinate from about eight to eleven o'clock in the morning. You only know how many flowers will appear the day before. It could be a few, but we once had to pollinate about 8,700 flowers in one morning. It is easy to imagine that this is a major challenge in terms of employment, because you do not know how many people you will need. In all the projects we've done so far, plant health and labor had been the breaking point that stood in the way of successful cultivation. Fortunately, we have been able to overcome both so far.”

Three kinds of vanilla

Inspired by the different stories, we close the door of the greenhouse behind us and drive back to Koppert Cress. There we meet Bart and Rob to explore the product/marketing strategy of the product. Bart: “We used the first modest yield of last year, a few thousand pods, to test the processing and taste. A vanilla pod is often still green when you pick it off the plant. Only by 'curing' the pod turns black. This is an enzymatic process in which the sugars from the pod are converted into vanillin and other substances that give the vanilla its characteristic smell and taste. We do this under the influence of moisture and temperature. We went through this process in several ways to find the best way. Culinary experts such as Hidde de Brabander and Onno Kokmeijer played an important role in this. Because what makes good vanilla, good vanilla? We were very curious about the expectations of our customers and whether we could possibly exceed them. At the moment that seems feasible.”

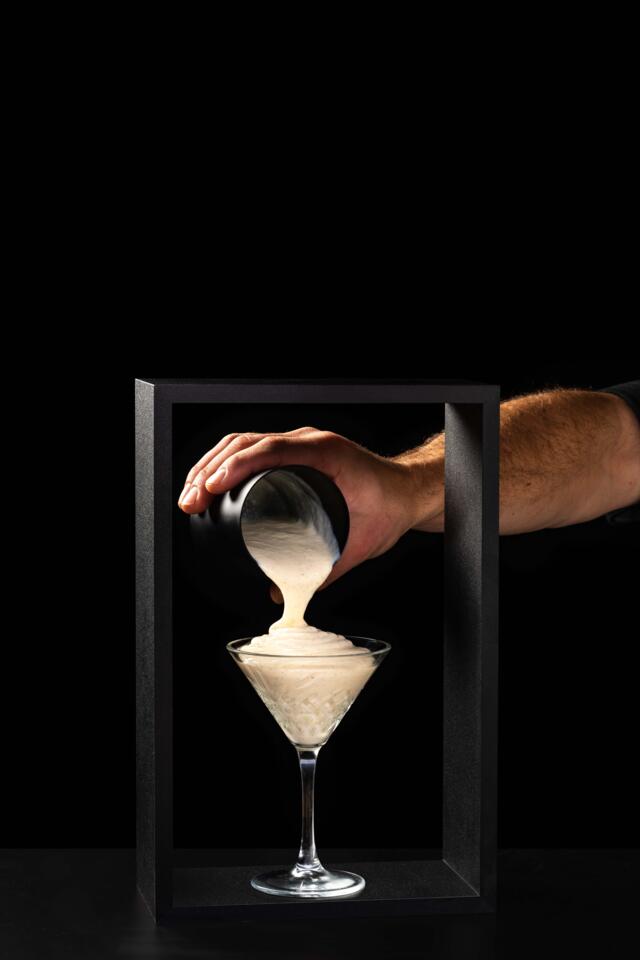

Rob: “All in all, we have decided to supply three types of vanilla products. Those three types actually evolved over time. In the beginning, it was our dream to grow traditional Planifolia. While working on that product we realised we could also introduce a red and green variant, which is not possible via the traditional route. First of all, the green pods that chefs, pastry chefs, ice cream makers, bartenders and other professionals can cure themselves, because what could be more fun than experimenting with your own processing process? Then you can start working on adding other scents. In addition to the green pod, we are introducing the black variety, which we cure in special ripening cabinets. And the third type of vanilla, we ripen on the plant; a vine-ripened vanilla, as it should grow naturally. This offers whole new possibilities, because by letting the pod hang on the plant longer, it gets an even better flavor profile. Vanillin is still the main flavour, but we have also found a number of side flavours.”

Culinary versatility

Master Patissier and SVH Master ice cream maker Hidde de Brabander has been closely involved in the development of the vanilla and was a regular in the kitchen of Koppert Cress to taste the different vanilla harvests. Hidde: “Vanilla is also known as the black gold or the caviar of the patisserie. And for a reason, if you zoom in on the seeds in the vanilla pod, you'll see the same shimmer as caviar, but much finer. It is truly the most classic, exclusive and luxurious aroma maker in pastry.” Vanilla is often known as an ingredient for, for example, ice cream, custard or crème brûlée, which almost made it feel like a commodity. Hidde explains: “At one point, vanilla was like salt and pepper, it was used almost everywhere. Until prices started to rise due to shortages due to bad harvests, after which the use of vanilla started to be revalued. The added value of vanilla is now not only in the aroma, but mainly in the re-evaluation of the position of vanilla: where do you add it and in what quantity? If you serve vanilla with scallops, the dish may seem sweeter, but it actually becomes rounder. Vanilla is a real friend to everyone and makes something sweet, but it is also luxurious.”

Yet we still wonder: what makes Koppert Cress vanilla so special, except that it is grown in the greenhouse? Hidde continues: “It's about the complexity of the aroma components. The pod is very fresh and therefore has an extra bit of green. I can best compare the taste to grapes; this vanilla is like a semi-dried muscat grape. It's not a raisin yet, it's much more than that. The plant-aged vanilla, the red one, is certainly out of this world. Basically it is grown exactly the same as the black variety, but by picking it much later, the taste is different. It's like chocolate: everyone is used to the simple, dark chocolate, but now you get a super exclusive chocolate that contains many more layers of aroma. These pods symbolize how vanilla should be naturally; they are fresher and fatter and therefore much less dried out, as we are often used to.”

It's the inside that counts

As soon as we grab a black vanilla pod we feel what Hidde means, the outside is still soft and you see the glint of a layer of moisture. Not what you expect from a vanilla pod. Hidde: “The jacket that contains vanilla is normally a bit dull (and though the outside of a vanilla bean isn't used most of the time) it is only when you open the jacket that you come across something beautiful. Some producers inject their vanilla pods with a substance that makes the pod appear thicker. If you cut that pod open, the content is extremely disappointing. So just like we say about humans: it's the inside that counts. And with the Koppert Cress vanilla you get what you see. A nice, full, thick bean with a lot of marrow, a lot of aroma and a high glucovanillin content.”

Meanwhile, the entire kitchen smells of the sweet scent of the Mexican product. We are suddenly aware of the world journey that vanilla has made over the years and how it has now ended up in the small country of The Netherlands. A beautiful plant, loved by many, with a surprising history. And because nature has much more to offer, we hope to be able to continue to bring surprises to the culinary world in a sustainable way.

Website: www.koppertcressvanilla.com

Instagram: @koppertcressvanilla

Source: Culinaire Saisonnier 104 - Spring 2022 (Dutch edition)